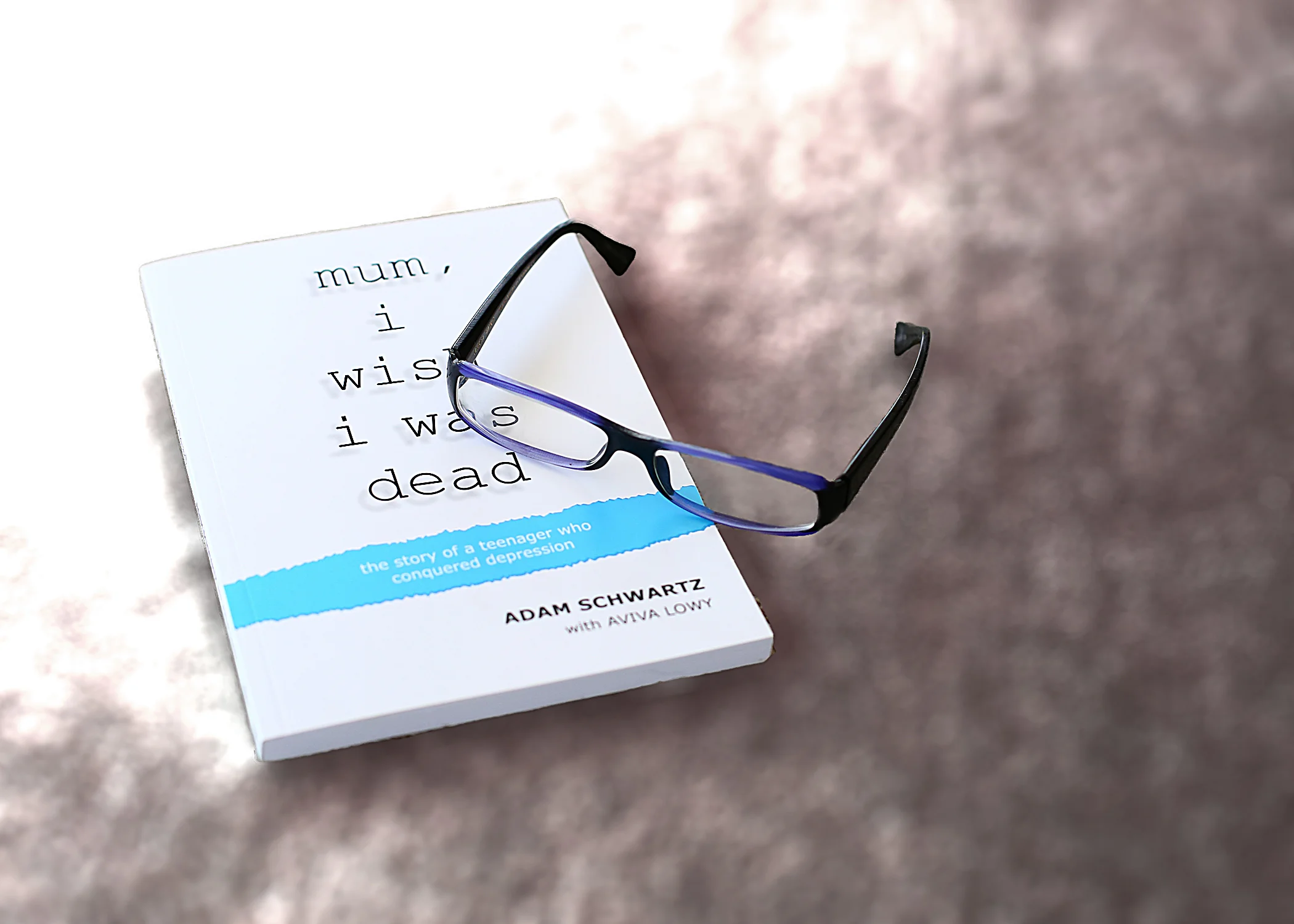

Adam Schwartz has chronicled his harrowing experiences of being a teenager suffering from depression in a new book,

Mum, I Wish I Was Dead, in the hope that his story will provide inspiration to other sufferers. Phoebe Roth reports.

FOR many months during his teenage years, Adam Schwartz could hardly get out of bed, let alone leave the house. He would cry himself to sleep every night, and couldn’t bring himself to look in the mirror in the morning.

Schwartz, now 24, traces his crippling battle with depression back to when he was 10.

“Mum reminds me that I said to her one day, ‘My heart is black, my body is full of anger, and I wish I was dead.’ At 10,” he tells The AJN.

That sentiment – the severity of which Schwartz says he didn’t really understand at such a young age – is the title of his book which was launched recently.

After that first period of illness at 10, which saw the Sydneysider out of school for a time, Schwartz seemed to have recovered. But a few years later, once he’d started high school, he fell ill again.

He suffered several bad bouts of tonsillitis and lost the ability to walk. He was hospitalised in the Sydney Children’s Hospital and underwent rehabilitation to learn how to walk again.

“It was never once suggested that it could be something psychological. Even now, looking back with hindsight, I was so miserable and unhappy,” says Schwartz.

Again, he got better and was able to experience life as a teenager for a little while, enjoying school, sport and socialising.

Around his 15th birthday, he dipped once more. He recalls that his family went away on a holiday, but he adamantly refused to go. One night, he slammed his fist on the dinner table, swore at his family, and stormed to his room. The trigger for this incident was trivial, and his behaviour utterly out of character.

“When my parents went to bed later that night I decided I was leaving. I was running away. And I ran away just to the park around the corner. Fortunately they heard me leave, and they found me lying on the gym equipment, tears rolling down my cheeks,” recounts Schwartz.

“That again was a time I said ‘I hate my life, I can’t keep doing this, and I wish I was dead’. And because I was a bitolder I actually understood what those words meant, and that that wasn’t okay to feel. That wasn’t okay to say. And I realised I needed help.”

From that point, Schwartz was referred to a psychiatrist, placed on numerousdifferent medications, and had his diagnosis changed from depression, to bipolar, to unipolar, and back to depression.

“I had to always wear the ‘everything’s okay’ mask. I put this smile on, and I laughed, so no one would know anything was wrong. Over those years not a single laugh, not a single smile, was ever because I felt it. It was always because I felt that’s what I had to do,” Schwartz recollects.

“There wasn’t a day that went by that I didn’t contemplate taking my life.”

Fortunately, Schwartz fought on – when he could no longer fight for himself, he fought for his family, who were suffering alongside him.

“I saw the damage the disease was doing to my family. I saw the effects it was having on my parents’ relationship. I saw the effects it was having on my younger brother, who was only 13. He used to hear me cry myself to sleep every night.”

When all hope was just about lost, shortly before Schwartz turned 17, he decided to get ECT (electroconvulsive therapy).

“It took two years to get to that stage. It was my last resort. If I wasn’t as bad as I was, I wouldn’t have got it. And I know for myself if it wasn’t an option, or it didn’t work, I wouldn’t be sitting here today,” he says.

He notes that although ECT saved his life, it’s not what allows him to be well today. He dropped out of school to concentrate on his health, which included seeing his psychologists regularly, exercising and becoming self-aware.

With his life back on track – he became a personal trainer and is now studying at university – writing a book was not initially on his radar. He was always open about his experiences, and constantly talking to people going through their own journey, or loved ones of sufferers.

“By the end of these conversations all these people had a look of hope on their face. That sort of reliefthat if I can explain as well as I did my experience and get through it, they could do that same thing,” says Schwartz.

About three years ago he began writing, but found it difficult to write himself. He was fortunate to be introduced to journalist Aviva Lowy, who took his words and put them on paper.

“It was never her interpretation of what I was saying. It was always my words. And no matter how important a message is, if the story’s not told properly, it gets lost,” he says.

Getting it published, however, wasn’t easy. Schwartz was knocked back by a number of publishers who said that while the story had potential, they weren’t able to market it.

“It was a bit of a slap in the face [that] no matter how valid and necessary and important the story was, and as well written as it was, if it was too much of a risk for them they didn’t take it,” says Schwartz.

But knowing how vital the project was, he opted to go down the self-publishing route.

“I wasn’t going to give up just because they didn’t think they could justify that expense. I was fortunate that I could still live at home and use my money that I’d saved to finance this.”

The book has been well received, with endorsements from the likes of Professor Patrick McGorry, a former Australian of the Year renowned for his work in the field of mental health.

Schwartz would one day like to see his book used in schools.

“If I had this book when I was younger, it would have alleviated a lot of suffering for me ... I would have known who to speak to. I could have given it to my parents to say, ‘This is what I’m going through’. I could have given it to my friends to say, ‘This isn’t my fault, it’s not my choice.’”

He hopes the book will give hope to readers who are suffering, as well as go some way to alleviating the stigma that he believes surrounds mental health.

“There’s no scan for [depression], there’s no blood test for it. So people think you’re making it up. As if it’s some choice. But it’s never been a choice. Why would I choose to be at home crying myself to sleep every night, wishing I was dead, not being able to speak to girls I like, not being able to live a life, feeling like a husk of a person? Why would anyone choose that?

“This is really something I believe that everyone needs to be exposed to. It can and does affect anyone. There’s no demographic immunity to it.”

Adam Schwartz will speak at Limmud-Oz in Sydney on June 7 at4pm on “Depression in Teenagers”.